When we think of Norse mythology, one of the first things that come to mind is the great deal of symbolism within it.

It simply is not possible to understand Norse faith without having a good grasp of Norse symbols and their meanings.

That is why we thought it is time to start going over them one by one. So, here comes Aegishjalmr/Aegishjalmur/Ægishjálmr, the Helm of Awe and Terror, one of the most prominent Viking symbols.

The Norsemen were a hardy race, battling the ravages of nature in some of the most inhospitable lands ever voluntarily populated by humans. The Viking warrior was tall, broad and muscular; fearless and universally feared in battle.

Through their legends, we know of one charm that conferred upon them the last two of those qualities: Aegishjalmr, the Helm of Awe and Terror.

Table of Contents

The Origin of the Name ‘Aegishjalmr/Aegishjalmr’

‘The name Aegishjalmr is a compound word comprised of two root words, ‘Aegis’ and ‘Hjalmr’. In Old Norse, Aegis meant ‘shield’ and Hjalmr meant ‘helm’.

The word ‘helm’ is itself the root word for ‘helmet’, a fact that becomes the source of an enormous amount of confusion over the interpretation of the word ‘Aegishjalmr’. The prevalence of the word ‘helmet’ over ‘helm’ among users of the English language has fueled the misconception that the name referred to an actual, physical helmet that was worn in battle.

In truth, a correct understanding requires one to stay loyal to the translation of the original root word, Hjalmr as ‘helm’. The word ‘helm’ means ‘at the forefront’ or refers to an elevated position that oversees all.

Thus, the Aegishjalmr really referred to a symbol that was marked on the forehead and between the eyes of the Viking warrior before battle.

We know this to be true from the Volsungasaga (Saga of the Volsung Clan), an Icelandic tome that dates back to the 13th century and speaks of the rise and fall of the Volsung clan.

In Chapter 18, one of the heroes of the saga, Sigurd, speaks to Fafnir, a man turned into a dragon by the curse placed on a hoard of gold he coveted, just before they do battle. Fafnir tells him of his exploits as a young warrior and speaks of the Aegishjalmr which gave him victory in every battle:

An ægishjálm I bore up before all folk… so that none dared come near me, and of no weapon was I afraid, nor had I ever seen so many men before me, and yet deemed myself stronger than them all; for all men were greatly afraid of me.

The Sorla þáttr, written by two Christian priests in the 14th century speaks of the Aegishjalmr as the ‘Helmet of Horror’.

In it, one warrior warns another not to look the enemy knight in the face because he wears the Aegishjalmr. However, the text seems to imply that the said helmet is a physical shield donned by the knight.

The Origins of the Aegishjalmr Symbol

When one studies the Aegishjalmr closely, it becomes fairly easily recognizable as a symbol of protection rather than an offensive one.

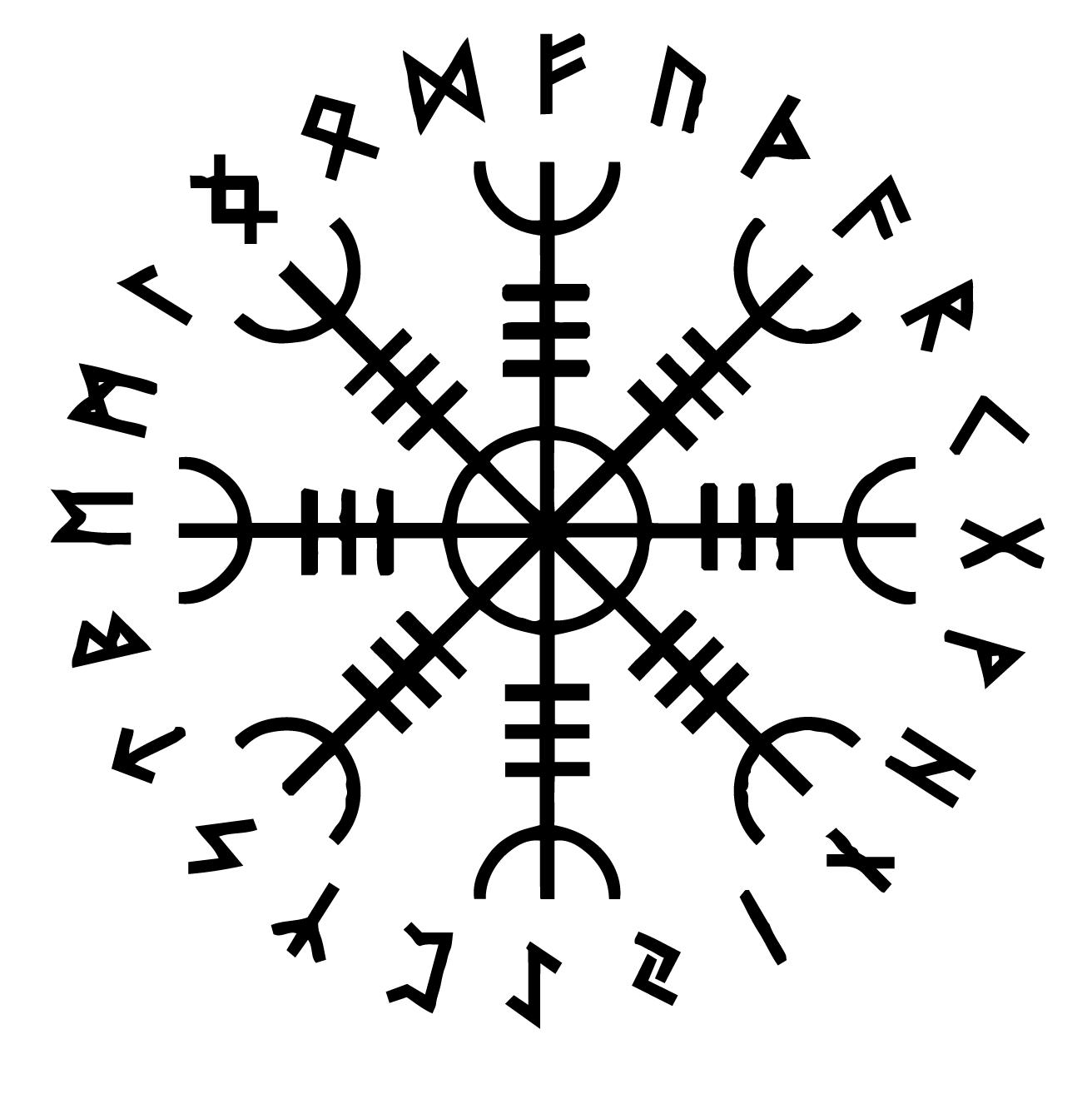

There is a circle at the center surrounded by eight prongs, four in the cardinal directions and four in between those. The ends of the prongs have three points each and may be represented as either curved or straight lines but are seen far more often in the former style.

Sometimes, the Aegishjalmr is shown with a circle of runes around it but this is a stylistic addition made in recent times and no actual Aegishjalmr has ever been found displaying that design.

The central circle represents the circle of protection within which the bearer is safe. This is a representation common to many cultures and is similar to the Magic Circle of protection and invocation used in Wicca.

The eight prongs represent protection against evil intent, perceived or otherwise, from all directions.

In the Aegishjalmr, it is believed that the presence of the crossbars strengthened the spell just as physical crossbars on an outward-pointing spear would afford greater protection in real life.

The eight points of the Aegishjalmr are actually tridents, a very common symbol in Hinduism. Shiva, the Destroyer of worlds, is always depicted in Hindu iconography as holding a trident, called a trishool in Sanskrit.

The Hindu trishool also often sports the same horizontal crossbars immediately under the trident head as seen in the Aegishjalmr. The three horizontal lines are also a very common ‘tilak’ or forehead marking among followers of Shiva. They may be drawn right across the forehead or just at the center.

There is abundant evidence of the shared roots of the European and Indian people, particularly through the migration of the Aryan people to the subcontinent.

However, there is also evidence that certain elements, particularly the trident shape may be of a more localized origin. The trident is sometimes depicted in the shape of the Algiz rune, which is the ‘z’ of the Elder Futhark runic alphabet. Algiz itself means ‘Elk’ and its shape is reminiscent of the animal’s antlers.

The Algiz has also been interpreted as a man with his hands up to the heavens in supplication or as a flower opening up to the sun, a metaphor for receiving the knowledge and protection of the divine world.

It may be so that the proto Indo-Europeans held the shape of the trident in high esteem before the original split of the two groups and that it came to be interpreted and represented in similar ways in the branching cultures it preceded.

How Did the Aegishjalmur Work?

There are various sagas which refer to the Aegishjalmur but none go into any detail of the mystery of its workings. There is a discernible difference between what the stave was said to be capable of achieving as a symbol in early stories and later ones.

In early tradition, the Aegishjalmur was applied to the forehead of the warrior using a stained image of the symbol carved into lead or copper. He then said the phrase “Aegishjalm I carry between my brows”. This ritual was said to assure victory in battle.

Later versions, dated to the 14th century onwards, when Christianity had been accepted by large swathes of the Scandinavian populations, saw the appearance of physical Aegishjalmr helmets that could be worn. These helmets had abilities far greater than the ones envisioned in the preceding sagas.

Placement

The placing of the Aegishjalmur between the eyes of the warrior is also an insightful clue to two things that we understand about the symbol today.

First and foremost, the placement tells us that the symbol would have been a small one. It was not emblazoned on the chest or upon the helmet; the entire intricate design had to fit within a space that was just about half an inch wide.

This hints strongly at the fact that Viking warriors did not see the Aegishjalmur as an object of physical intimidation.

It is completely unlike, say, a terrifying horned mask bearing a menacing countenance that would act as a source of dread and strike fear in the hearts of enemy troops who laid eyes upon it.

No, the Aegishjalmur was a personal charm. It would probably never even have been perceived by an opposing warrior for its small size.

This would be particularly true in the heat of battle, where the movements of attack and defense by the warrior bearing the charm would render it virtually indistinguishable from his face.

The second thing at which the placement hints is again the origins of the symbol. Placing a mark between the eyes is a prominent aspect of the Indic religions because it was believed to be the location of the mystical Third Eye.

In eastern traditions, your left and right eye see the physical world. The Third Eye, located between them, is the Mind’s Eye.

It perceives all things beyond the apparent or physical. This idea gels perfectly with the Aegishjalmur’s ability to induce awe and terror in the mind of the opponent even before the battle is joined.

The design of the Aegishjalmur gathered energy at the point where it could be projected out upon its intended targets (who would be seen as aggressors that intended to do the bearer harm). The Third Eye sought out signs of weakness within them that would fall prey to fear and terror.

It then unleashed those individuals’ greatest fears to protect the bearer.

When Fafnir spoke in the Volsungsaga, “…none dared come near me…”, this was perhaps the truth of the Aegishjalmur’s power to which he alluded.

Seidr (say-der)

Seidr is a branch of Old Norse magic that dealt with fate. Masters of seidr could perceive the lines of fate woven into the existence of a particular person or thing and alter it minutely to affect its future, rewriting the hand of destiny.

In practice, seidr was said to be able to cloud the perception and judgement of the people in the vicinity of the practitioner, usually a woman.

They could make things appear unlike their true form, make an observer completely miss something (hide something or someone in plain sight) or even forget something that they did see.

It was the first of those three that the Aegishjalmr would have to achieve for it to work on the battlefield. It is thought that wearing the stave made the people around the warrior, both friend and foe, perceive him differently.

To those who fought by his side, he would be a vision of fearless power and battle readiness, ready to cleave the enemy with his individual weapon and lead them collectively to resounding victory.

Soldiers on the opposing side would see a terrifying vision of an invincible warrior that they had no chance of defeating and would lose heart at his very sight.

It is unclear, though, how the seidr would work on a warrior through the Aegishjalmr. From all accounts, seidr only works within a given area around the shaman or witch; the more powerful and skillful they are, the larger the circle and the people over which they can hold their spell.

However, an Aegishjalmr is worn by the warrior and not by the practitioner of magic. Would a blessed spell cast directly upon the warrior with the stave have the ability to convey the same illusions that only the magician could control?

Certainly, warriors were not magicians in the same way that we do not have fighter pilots who are Navy SEALS today. In that sense, if the Aegishjalmr did work via seidr, it would have been of a form of which we no longer have any knowledge.

Invisibility and Other Gifts

Invisibility is perhaps the aspect that is least well-known and also the least supported by much of the surviving literature of the age of the Vikings. It is alluded to in later material, when the Aegishjalmr is considered a physical helmet, quite unlike what was imagined in its first iterations.

Again, exact descriptions and pictures are non-existent and one can only surmise from the material that it was shaped to a point, much like the hats wizards and witches were supposed to have worn.

Pointed hats were always associated with improvement of mental acuity and prowess; in fact, the ‘dunce’s hats’ that children were forced to wear in school were shaped such for that very reason.

Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle (Der Ring des Nibelungen) takes the idea to fantastic extremes with an Aegishjalmr named Tarnhelm conferring upon its wearer the ability to not only become invisible, but shape-shift and even teleport.

It is perhaps a sign of the times that the warrior’s stave of invincibility is today sometimes promoted as some sort of love spell to ‘guarantee victory’ in the bedroom. Needless to say, the Aegishjalmr does not do anything of the sort and was never meant for inane pleasure-seeking. It is a construct of a time when life was harsh and brutal, and death was ever-present.

The Life of an Aegishjalmr

It was not so that once the symbol was applied to a warrior, he would forever be invincible; the magic behind Aegishjalmrs was finite. No material exists that alludes to the exact longevity of the spell and it is unclear whether it lasted for a skirmish, a battle or a campaign.

However, it is clear that it did follow a rule of diminishing returns. In the Volsungasaga, when Fafnir taunts Sigurd with the feats he has performed and the warriors he has killed he has killed using his Aegishjalmr, Sigurd replies:

Few may have victory by means of that same ægishjálmr, for whoever comes among many shall one day find that no one man is by so far the mightiest of all.

Liked our Aegishjalmr post? Share it if you could! Many thanks.